GMO Skepticism, Scientific Knowledge, and Cognitive Consistency

Brief Report August 30, 2024 by Clint McKenna

There exists a common misperception that genetically modified foods and organisms (GMOs) are more harmful to consume than non-GMO products, despite scientific investigations maintaining their safety. 1 Europäische Kommission, & Direktion Biotechnologien, L. und E. (2010). A decade of EU funded GMO research: (2001-2010). Luxemburg: Publ. Office. For instance, according to a recent Pew survey, 49% of Americans believe that GMO foods are worse for one’s health when compared to non-GMO foods. 2 Kennedy, B., Hefferon, M., & Funk, C. (2018, November 19). Americans are narrowly divided over health effects of genetically modified foods. Retrieved March 14, 2019, from Pew Research Center website: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/11/19/americansare-narrowly-divided-over-health-effects-of-genetically-modified-foods/ Despite these hesitations, GMO foods include many benefits, like the ability to increase crop yield, resistance to pesticides, or alteration of taste. What are the underlying reasons for people's resistance to GMOs, and what do these insights suggest about the way humans process information?

Past research has found that those skeptical of GMO products tend to be the least knowledgeable about them, despite self-reporting more knowledge. 3 Fernbach, P. M., Light, N., Scott, S. E., Inbar, Y., & Rozin, P. (2019). Extreme opponents of genetically modified foods know the least but think they know the most. Nature Human Behaviour, 3(3), 251. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0520-3 To make more sense of this, we can also look to how people process conspiracy theories. Research by Joanne Miller and colleagues (2016) examined conservative-leaning conspiracy theories and whether greater levels of general knowledge and trust mitigated some of the implausible beliefs. 4 Miller, J. M., Saunders, K. L., & Farhart, C. E. (2016). Conspiracy Endorsement as Motivated Reasoning: The Moderating Roles of Political Knowledge and Trust. American Journal of Political Science, 60(4), 824–844. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12234 These beliefs included the beliefs like Barack Obama was not born in the U.S., or that the Bush administration knew about 9/11 before it happened. The authors found that participants at higher knowledge were actually surprisingly more polarized, such that there was more polarization in beliefs between more knowledgeable liberals and conservatives. Finally, this moderating effect of knowledge was itself conditional on trust; for individuals who were high in trust, the belief among conservatives was lower when compared to those low in trust.

Cognitive Consistency

Why might people with more knowledge have more biased beliefs? We are interested in how cognitive consistency between one's thoughts can mitigate some implausible political beliefs. Decades of research on cognitive dissonance suggest that individuals attempt to resolve inconsistent attitudes and behaviors. 5, Cooper, J. (2007). Cognitive dissonance: fifty years of a classic theory. Los Angeles: SAGE. 6 Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

How can this affect political or moral beliefs? Research by Liu and Ditto (2013) provide evidence for a "moral coherence" view. 7 Liu, B. S., & Ditto, P. H. (2013). What Dilemma? Moral Evaluation Shapes Factual Belief. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(3), 316–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550612456045 When individuals view an act as morally wrong, they will also rate the positive consequences as less likely to happen. For instance, when evaluating if providing condoms to teenagers would be likely to reduce STD and pregnancy rates, individuals who viewed the action as morally wrong report a lower likelihood that it would be an effective intervention anyway.

In the case of GMO foods, a moral coherence approach would dictate that individuals who believe GMOs to be harmful for one’s health will also believe they will not be beneficial to society.

GMO Harms and Benefits

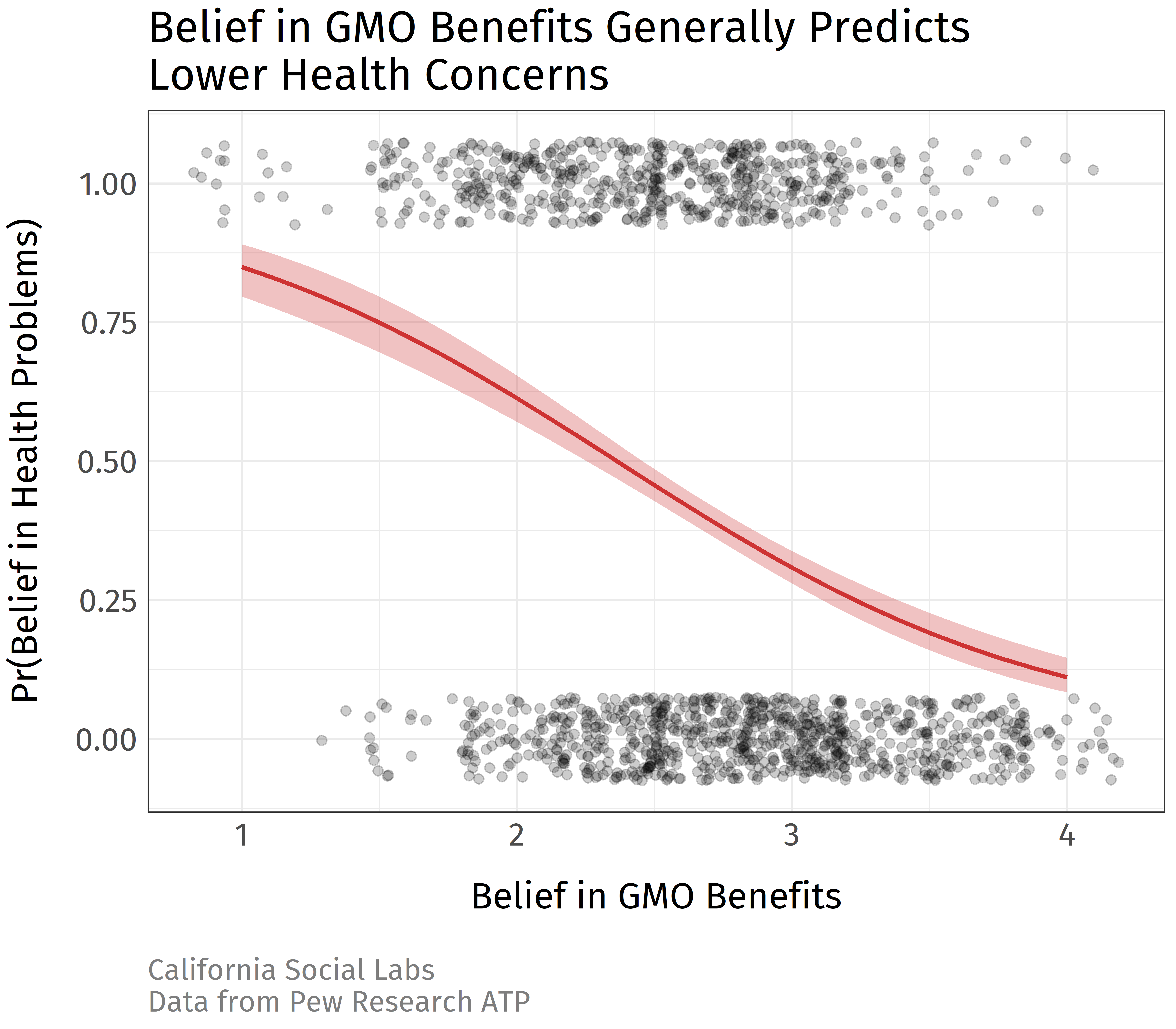

Given past research, we wanted to dig in to some beliefs about GMOs, and how they influence health concerns. Examining data from Pew Research Center American Trends Panel, we first looked at how perceptions of positive aspects of GMOs (being more affordable, leading to less environmental problems, and creating a greater global food supply) predicted the belief that GMOs could lead to health problems. In the data, people who held this belief (or leaned towards it) were compared to those that either did not hold this belief or were ambivalent (which was by far most respondents).

As we are treating the outcome of the health problem belief as a binary outcome, the y-axis is either 1 or 0, with each point being a respondent who either holds this belief or not. As you might expect, as beliefs in the benefits of GMOs increase, the belief that GMOs lead to health problems decrease in likelihood. The fitted red line follows this estimated probability at different levels of beliefs: health concern endorsement decreases as respondents are more favorable to the societal benefits of GMOs. This makes sense if someone views GMOs as generally good or bad, and thus judges the consequences of GMOs based on if it is consistent with their global feelings.

Scientific Knowledge

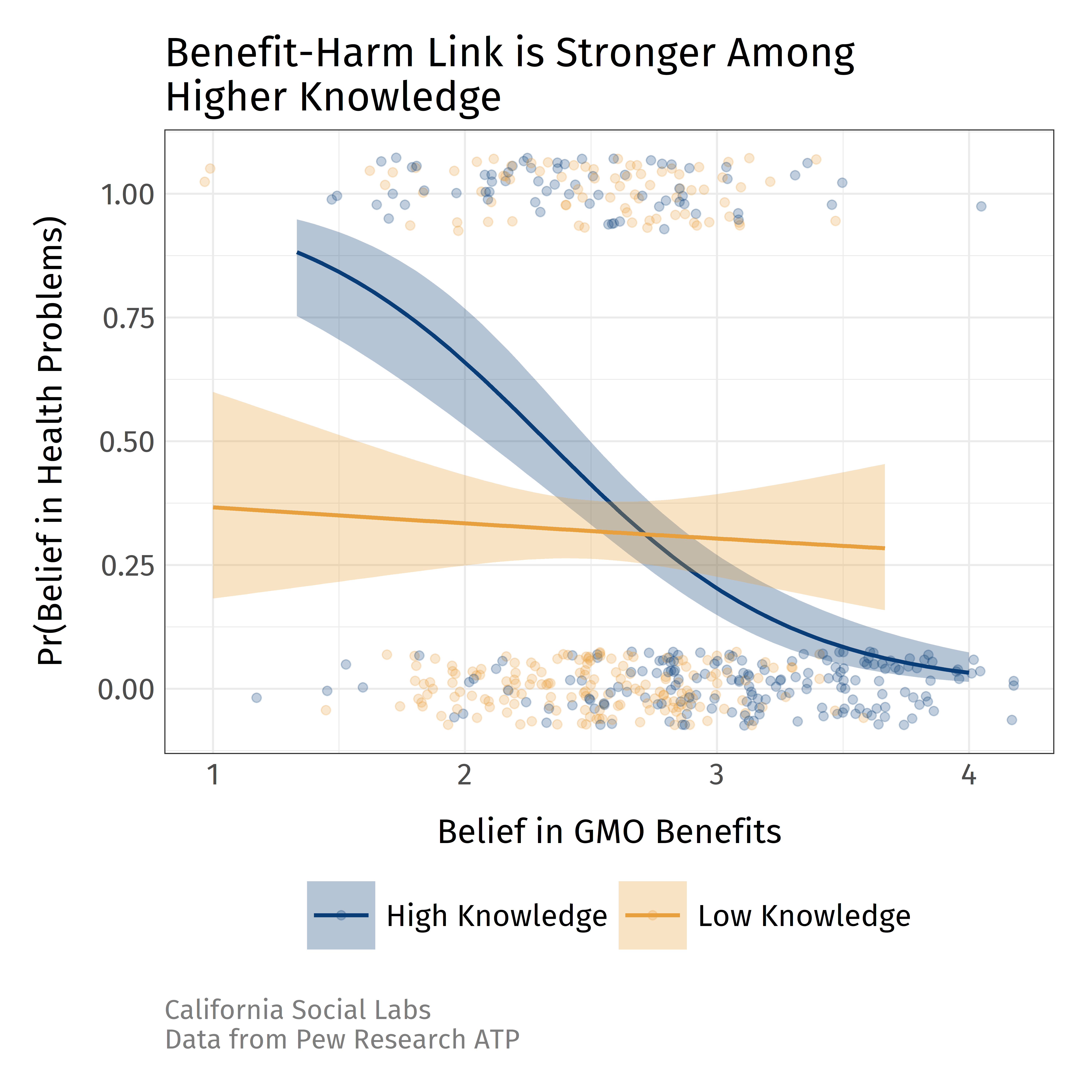

How does this relation change based on the scientific knowledge of the respondent? Using an index that tests respondent knowledge of basic scientific facts and phenomena, we looked at how the benefit-harm link changes.

For the sake of visualization, we broke down scientific knowledge into two groups: high and low. Our analysis revealed a striking contrast between high and low scientific knowledge participants regarding the relationship between perceived GMO benefits and health concerns. Among high knowledge participants, we see that there is a strong negative relation: as benefit beliefs increase, health concerns decrease. However, this was not as strong for those with low scientific knowledge.

Why might this be? One explanation for this difference could be that highly knowledgeable people desire to be more coherent in their beliefs, leading them to downplay potential health concerns as their appreciation for the benefits of GMOs grows. An alternative explanation could be that lower knowledge respondents might simply be less aware of the benefits of GMOs, regardless of whether or not they share any health concern beliefs.

Trust

What about how trust influences these relations? While our analysis uncovered that individuals who generally trust scientific institutions and experts tended to have lower concerns about GMO health risks, trust was not as influential as one's scientific knowledge in shaping these beliefs. Moreover, trust did not alter the established link between perceived benefits and health concerns, nor did it modify the moderating role of scientific knowledge on this relation.

Conclusion

The skepticism surrounding GMOs is affected by a complex interplay of scientific knowledge, cognitive consistency, and trust. Our findings suggest that individuals with a deeper understanding of scientific principles are more likely to be coherent about their beliefs about the benefits and potential risks of GMOs. While trust plays a role in shaping public opinion, it seems to be less influential than scientific knowledge in fostering cognitive consistency.

Given our case study of GMOs, it may be useful for policy makers to leverage cognitive and moral coherence as they implement educational programs for moralized issues. By understanding attitude dynamics in the perceptions of policy effectiveness, public resistance to beneficial interventions could be quelled.

Political reports by California Social Labs should not be interpreted to endorse or support any particular political group, candidate, or legislation.

Data and code are available at https://github.com/CaliforniaSocialLabs/gmo-knowledge Participants. Data examined 1403 participants from Pew Research Center's American Trends Panel Wave 17. Participants were 51.7% Female, 48.3% Male. Participant age groups: 12.4% 18-29, 29.5% 30-49, 29.9% 50-64, 29.1% 65+. Measures. Outcome variable was dichotomized as following: coded 1 for supporting the belief that GMOs lead to health problems (or lean this way), coded 0 for being not sure or believing they do not (or lean this way). The rationale for dichotomizing was that the distribution was heavily skewed towards either being unsure or convinced of health problems, accounting for 87.2% of all responses. GMO Benefit beliefs were the average of 3 items related to the belief that GMOs will make (1) food more affordable, (2) increase the global food supply, and (3) increase environmental problems (reverse-coded). Scientific knowledge was a summed index of 10 items testing respondent knowledge. This index included general scientific knowledge items like the following: "Which of these terms refers to health benefits occurring when most people in a population get a vaccine? (a) Herd immunity, (b) Population control, or (c) Vaccination rate" or "Which of the following can be genetically modified? (a) An apple, (b) Salmon, (c) A mosquito, (d) Corn, (e) None of these." Trust was the average score of responses to 5 targets: "How much, if at all, do you trust each of the following groups to give full and accurate information about the health risks and benefits of eating genetically modified foods? (a) Elected Officials, (b) Scientists, (c) Food industry leaders, (d) The news media, and (e) Small Farm Owners." Model Results. In the primary model (χ²(3) = 216.326, Pseudo-R² = .114),the main interaction of benefits x knowledge revealed a significant interaction term, OR = .699, 95% CI [.63, .776], p < .001. The slope of GMO benefits predicting health concerns was significantly more negative at +1 SD (b = -2.145, p < .001) when compared to respondents at -1 SD (b = -.453, p = .006). In the interaction plot depicted above, the fitted lines represent a simple logistic regression for all respondents in either +/-1 SD in scientific knowledge.

1 Europäische Kommission, & Direktion Biotechnologien, L. und E. (2010). A decade of EU funded GMO research: (2001-2010). Luxemburg: Publ. Office. 2 Kennedy, B., Hefferon, M., & Funk, C. (2018, November 19). Americans are narrowly divided over health effects of genetically modified foods. Retrieved March 14, 2019, from Pew Research Center website: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/11/19/americansare-narrowly-divided-over-health-effects-of-genetically-modified-foods/ 3 Fernbach, P. M., Light, N., Scott, S. E., Inbar, Y., & Rozin, P. (2019). Extreme opponents of genetically modified foods know the least but think they know the most. Nature Human Behaviour, 3(3), 251. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0520-3 4 Miller, J. M., Saunders, K. L., & Farhart, C. E. (2016). Conspiracy Endorsement as Motivated Reasoning: The Moderating Roles of Political Knowledge and Trust. American Journal of Political Science, 60(4), 824–844. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12234 5 Cooper, J. (2007). Cognitive dissonance: fifty years of a classic theory. Los Angeles: SAGE. 6 Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press. 7 Liu, B. S., & Ditto, P. H. (2013). What Dilemma? Moral Evaluation Shapes Factual Belief. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(3), 316–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550612456045